A review of ‘Human Rights Issues in maternal health care in Kenya: Do Kenyan women enjoy the right to maternal health?’ and ‘Barriers to enjoyment of health as a human right in Africa’ provides a useful background to the case studies.

The recently launched report by the Kenya National Commission on Human Rights[i] highlights several incidents and situations where women were denied their right to health care services both because of non-availability of resources and non-affordability of services, as well as misdeeds on the part of health care providers. People living with disabilities (PWDs), in particular, complained of mistreatment, especially delays in getting attended to in health facilities. Most health institutions were not disabled-friendly in terms of infrastructure and means of communication, for example, facilities for sign language or Braille.

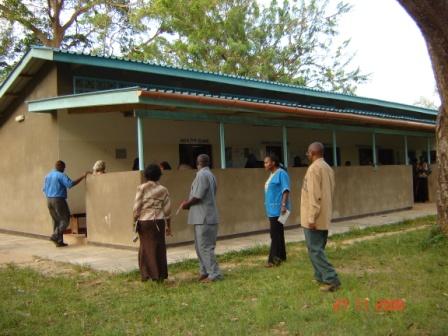

A Level 2 Health Facility at Mtwapa, Mombasa County (Picture: J Mati)

Witnesses raised several complaints related to the inefficient referral systems in several health facilities that caused considerable delays in obtaining higher level care, not infrequently resulting in fatal consequences for the women and their babies. This was particularly a serious problem when it came to referral of patients from levels 1 and 2 to appropriate higher level facilities.

In some cases, women in rural areas had to be transported on wheel barrows by family members or on donkey carts. Where hospitals had ambulances, the patients or the relatives were required to pay amounts ranging from KSHs. 500 to KSHs. 3,000 supposedly to fuel the vehicles. In situations where people were unable to pay, patients were denied treatment. In other instances, blood was not readily available in hospital blood banks, or the facilities lacked adequate infrastructure to obtain blood for emergency transfusions.

In Tana River, for example, a woman who developed complications after delivering at a dispensary (level 2) died while waiting to raise funds, through harambee, to fuel a government ambulance to take her to Hola District Hospital. A similar report is given in connection with a maternal death due to lack of transport between Magarini Dispensary and Malindi District Hospital, both in Kilifi County.

In Lamu County, patients who needed to be referred to Coast Provincial Hospital in Mombasa were reportedly required to pay between KSHs. 8,000 and KSHs. 10,000 to fuel the hospital’s ambulance. Where there are no ambulances, as in Wajir and Marsabit District Hospitals families had either to hire expensive taxis or resort to donkeys and camels to transport their sick members.

Witnesses testified that the high cost of hospital delivery, especially the fees charged at level 4 and 5 facilities, was a key hindrance to accessing skilled attendance at delivery. A witness during the inquiry stated thus: ‘Many women deliver at home because they do not have enough money to go to the hospital’.

Corruption, especially among hospital management staff, was also cited as a barrier to accessing maternal health services. According to witness accounts from Kitale, corruption in health facilities meant that patients ended up paying for drugs and other items that ought to be provided for free. Similarly, bribes were solicited to facilitate earlier scheduling of surgical treatment, as stated by a witness at the Coast: “For one to get an operation done quickly at Coast General Hospital one has to pay bribes or know someone because there are long queues, so I left”.

Mistreatment in health facilities by unkind, cruel, sometimes inebriated hospital staff, who scolded, abused and even beat patients also features prominently in the report. So are delays in getting attended to in health institutions, particularly in the labour ward, where witnesses complained of being neglected during labour, in some cases ending in delivering unattended within the hospital. An example is the case of a woman who waited at the out-patients from 5am to 4pm before being admitted to the labour ward, ending up with a stillborn child. Women complained of being admitted in overcrowded wards and sharing of beds; up to three women with their babies sharing one bed, even when some of them were still bleeding, which exposed them to potential risk of infection, including HIV and Hepatitis B. Detaining of women for non-payment of hospital charges obviously contributes to congestion in hospital wards.

There were complaints of frequent lack of essential medicines, equipment, commodities and supplies in public health facilities resulting in denial of services to the needy. It was common in most public facilities for patients to be asked to purchase medicines, gloves and dressings, besides being referred to private institutions for specialised radiological and ultrasound diagnostic examinations. Essential resources for effective provision of sexual and reproductive health services were lacking in many health facilities. For example, many lacked the drugs needed for post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) following sexual abuse including rape. The Inquiry established that non-availability of family planning commodities was a fundamental barrier to accessing comprehensive family planning in Kenya, this being illustrated by the frequent stock outs of commodities. There were complaints of frequent shortages of various contraceptives which denied clients a wide choice of family planning methods.

Several witnesses complained of negligent actions by doctors and midwives, for example, forgetting items such as surgical instruments or swabs in a patient’s abdomen; performing procedures such as hysterectomy without prior informed consent; poorly managed labour leading to ruptured uterus, maternal morbidities such as VVF and RVF, intra-uterine foetal death or a mentally handicapped child,. Other examples of negligent actions or omissions were performing episiotomy and failing to repair it, and failure to recognise accidental injury during surgery and failing to repair it immediately. There were women who complained that not enough information was given to them about the various diagnostic and treatment modalities they had been subjected to by health providers. In particular, there was inadequate information given to the patients before and after surgical procedures.

The Report cites an article published in The Daily Nation Newspaper of 18th January 2011 on a case of maternal death associated with abortion:

“A woman aged 40 years who was held at Murang’a police station for allegedly procuring an abortion died after she developed complications while in the police cells. The Police said the woman was reported to have terminated the pregnancy by swallowing some chemical, and locked her up in a cell at the police station. They said she later developed complications and was being rushed to hospital when she died en route.”

It can be argued that had the police taken the woman to a health care professional, instead of holding her in remand at the police station, she most likely would have survived. In other words this was a case of preventable death associated with denial of enjoyment of right to health. Yet this was after the promulgation of the Constitution of Kenya 2010 which has relaxed the rigidity on termination of pregnancy that existed previously. Article 26 (4) permits safe abortion if in the opinion of a trained health professional, there is need for emergency treatment, or the life or health of the mother is in danger, or if permitted by any other written law.

What can be learned from the above case studies?

Clearly, they demonstrate that Kenya has yet to address the well known factors and barriers that have over the years sustained the prevailing high rates of maternal and newborn mortality and morbidity. Maternal health services that are inaccessible, non-affordable and of poor quality, have been perpetuated by several serious weaknesses in the health systems- inadequate capacity in terms of human resources and health infrastructure, negligence and malpractices especially among over-worked de-motivated health service providers, and various socio-cultural barriers, among others. Addressing these barriers is a prerequisite to meeting local and international goals and targets including the Vision 2030 and Millennium Development Goals.

[i] A Report of the Public Inquiry into Violations of Sexual and Reproductive Health Rights in Kenya