The full enjoyment of the ‘Right to Health’ in most African countries is constrained by several pervasive barriers that are the subject of the current review, which urges that governments urgently adopt human rights based approaches to all health interventions in order to ensure equitable distribution of health resources throughout all sections of communities.

The Concept of Health as a Human Right: Health is a basic need for human existence and survival and as such, it is a right that must be respected, promoted and protected by government and society. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights states that “Everyone has the right to a standard of living adequate for health and well-being of himself and his family”. The concept of health as human right is stated in the Preamble of the World Health Organization’s Charter (1946), and also in the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (1966). Art. 12 states of health as a human right: “the right of everyone to the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health”. The Declaration of Alma Ata (WHO, 1978) stated: “Health, which is the state of complete physical and social well-being, and not merely the absence of infirmity, is a fundamental human right…. the attainment of the highest possible level of health is a most important worldwide social goal.” The right to health is fundamental to the physical and mental well-being of all individuals and is a necessary condition for the exercise of other human rights including the pursuit of an adequate standard of living. Indeed health is fundamental to enjoyment of the right to life, and the right to a healthy life is fundamental to all other constitutional guarantees.

Right to Health is a Constitutional Issue Besides the South African Constitution[i], the Constitution of Kenya (2010), which was promulgated in August 2010, is among the most progressive constitutions in Africa. It provides for the right to health care services. Article 43(1)(a) in the chapter on Bill of Rights states that every person has the right to the highest attainable standard of health, which includes the right to health care services, including reproductive health care, and in Article 43(2), that a person shall not be denied emergency medical treatment. Further, Article 27(2) guarantees equality and freedom from discrimination, and the full and equal enjoyment of all rights and fundamental freedoms. The Constitution obligates the government to take legislative, policy and other measures to achieve the progressive realization of the rights as guaranteed in the Constitution, including the right to health. The Right to Equality encompasses within itself the right of a poor patient to quality health care, regardless of their ability to pay.

Right to reproductive health care services: The concept of reproductive rights as a fundamental human right was endorsed at the 1994 International Conference of Population and Development in Cairo, Egypt. The constellation of rights, embracing fundamental human rights established by earlier treaties, was reaffirmed at the 1995 Fourth World Conference on Women in Beijing, China, and in various international and regional agreements since, as well as in many national laws. They include the right to decide the number, timing and spacing of children, the right to voluntarily marry and establish a family, and the right to the highest attainable standard of health, among others.

That reproductive rights are central to meeting international development goals was recognized by the UN World Summit of September 2005, which also endorsed the goal of universal access to reproductive health. Reproductive rights are recognized as valuable ends in themselves, and essential to the enjoyment of other fundamental rights. Attaining the goals of sustainable, equitable development requires that individuals are able to exercise control over their sexual and reproductive lives.

Right to reproductive health care services is explicitly recognised in the Constitution of Kenya (2010), just as it is recognized or implied in several international and regional instruments (see above), including the United Nations Millennium Development Goals (2000); the Maputo Plan of Action on Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights (2006); and the Campaign on Accelerated Reduction of Maternal Mortality in Africa (CARMMA) (2009).

Barriers to enjoyment of Right to Health

1. General issues

Enjoyment of right to health in Africa, besides the inadequate financing of the health sector (see below), is indirectly constrained by several factors that operate at the regional and national levels, and mostly outside the mandate of the health sector. These include poverty, food insecurity and hunger, persistent violent conflicts and displacement of persons, heavy disease burden especially due to HIV and AIDS, and the pervasive gender-based negative traditions such as early marriage, female circumcision and lack of women’s empowerment all of which have profound effects on reproductive health outcomes.

2. Inadequate Funding to Health sector

Many governments in Africa have yet to recognise the importance of health in the overall national development, and expenditure on health is not adequately perceived as a critical economic investment alongside spending on education, agriculture or industries. Health is a critical resource for development, without which investment in all other sectors would go to waste. Poor health impacts negatively on economic productivity, through loss of labour, and under-performance due to illness. Poor health creates critical barriers to any measures intended to uplift the social wellbeing of poor and disadvantaged communities.

The levels of health budgets in most African countries do not demonstrate that health is rated as a high priority among other national needs. Despite the fact that in 2001 African countries pledged in Abuja, to increase health sector budgetary allocation to 15% of government expenditure, and although they repeated this pledge in Kampala in July 2010, in most countries national budgetary allocations for health remain far below this target. A 2007 report of the Regional Network for Equity in Health in East and Southern Africa (EQUINET)[ii] which looked into the progress made in various Southern and East African countries towards achieving the Abuja target, showed that with few exceptions most of the countries were still lagging far behind this target seven years since the declaration.

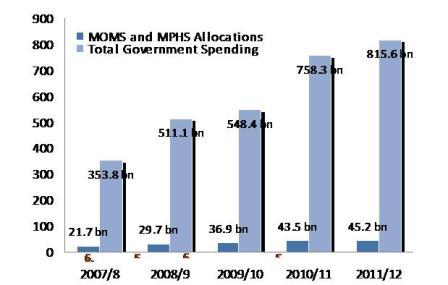

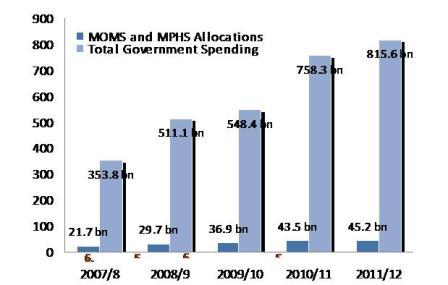

In Kenya, for the fiscal year 2010-11 just about 5.5 percent of the total Government expenditure was allocated to the ministries of Medical Services and Public Health and Sanitation. This translates to less than $1 per capita expenditure, against the recommended figure of $34 which WHO recommends for effective implementation of health interventions.

Figure 1: Real gross expenditure to the health sector, compared to overall gross Kenya Government expenditure (2007/08 – 2011/12)[iii]

A concern of particular relevance to achieving MDG5 is the disproportionate allocation within the health budget to reproductive health care services. Africa Union’s Maputo Plan of Action for Universal Access to Comprehensive Sexual and Reproductive Health Services in Africa (2007-2010) recommended an increase in per capita expenditures to about 18-24% of the $34 per capita recognized by the WHO. However, in many countries the allocation remains much below these figures.

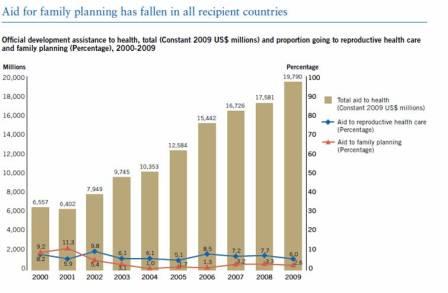

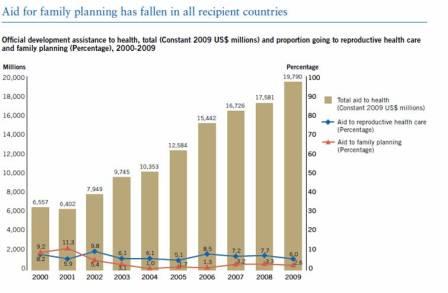

At the international level, global assistance for reproductive health including family planning, financing has fallen in all recipient countries. Figure 2 shows that whereas there has been a steady increase in overall assistance for health, the amount focused on reproductive health and family planning has remained more or less unchanged since the year 2000.

Figure 2: Total international assistance to health and allocation to reproductive health care programmes (2000-2009)

Source: The Millennium Development Goals Report 2011

3. Lack of Equity in Planning for health and distribution of resources resulting in inequitable Access to Health Care services:

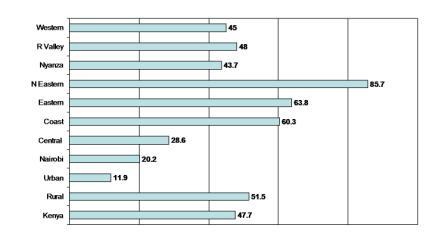

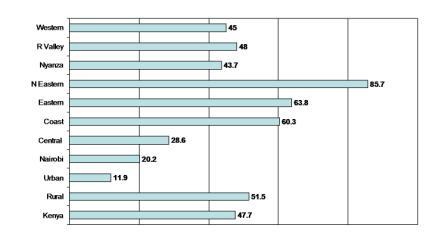

Physical access to services (distance to nearest Health Facility): Health care utilization is known to be greatly negatively impacted by distance to health care facilities and access to means of transportation. A study[iv] in western Kenya which explored the impact of distance on utilisation of sick child services in rural health facilities established that for every 1 km increase in distance of residence from a clinic, the rate of clinic visits decreased by 34% from the previous kilometer. According to the Kenya National Bureau of Statistics[v], on average only 6.4 percent of people in Kenya can reach a health facility within one kilometre of their residence; nearly a half (47.7%) of the people have to travel 5km or further to reach the nearest health facility, with marked regional variations (Table 1).

Figure 3: Proportion of community that has to travel 5km or more to the nearest health facility in Kenya

(Source: The Kenya Integrated Household Budget Survey (KIHBS) 2005/06).

For example, the proportion of people who live 5km or further from the nearest health facility ranges from 20% and 29% respectively in Nairobi and Central regions to 60%, 64% and 86% respectively in Coast, Eastern and North Eastern regions. The geographical dimension must be taken into consideration when planning health care interventions, especially when targeting socio-economically disadvantaged groups.

Affordability of services: Big disparities exist between the poor and the better off with respect to access to health care services which explains the wide gaps in health outcomes not only between rich and poor countries, but also between the wealthy and the poor in most countries. Generally, the poor lack access to health care in terms of: availability, affordability, and acceptability. Poor people are denied access to health care: (a) where public health facilities lack essential drugs, supplies and commodities; (b) where people have to travel long distances to reach health facilities, especially where public transport is scarce; (c) when fees charged for services (cost-sharing) are unaffordable, and even if there is official exemption (e.g. for pregnant women and children under five) or waiver of fees, people still end up paying on top, for drugs and transport (out-of-pocket expenditure); and (d) where people lack confidence in the services provided at local public health facilities and decide not to utilise them (e.g. poor quality services or negative provider attitudes).

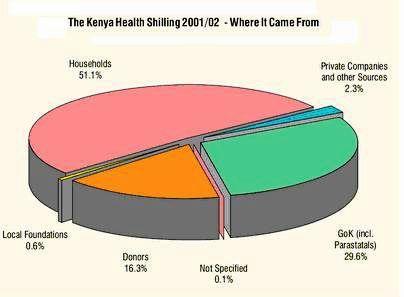

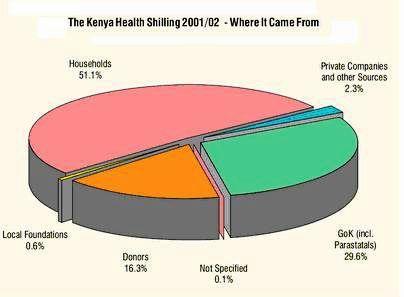

The poor bear the heaviest burden of out-of-pocket health expenditures, irrespective of where they seek health care. In Kenya, data from the National Health Accounts (NHA) for fiscal year 2001/2002 showed that Kenyan households were financing over half of all health expenditures[vi], clearly justifying a conclusion that ill-health contributes to, and perpetuates, poverty because health costs deplete people’s meagre resources. In addition, there is considerable evidence to suggest that by and large public spending on health tends to benefit the better off more than the poor. Quite often it is the better off who get the most from public health services, especially hospital care. In other words, government’s investment in health services, far from promoting equity, works against it[vii].

FY 2001/2002 National Health Accounts (NHA) estimation in Kenya

Inadequate financing of the health sector and inequitable distribution of resources explain the major gaps and disparities in health indicators in most African countries, which have featured repeatedly in successive surveys such as the Demographic and Health Survey (DHS). It is important to realise that because of the size of the poorest population, countries cannot hope to achieve health-related MDGs without urgent implementation of inclusive policies in the planning of health interventions.

Addressing barriers to enjoyment of right to health

Governments must strive to address the pervasive barriers to enjoyment of right to health (including sexual and reproductive health) by all citizens by implementing human rights based approach to all interventions aimed at improving the health of the community. This will empower people to participate in decision making and health policy development, as well as strengthening their capacity to hold the health managers and providers accountable. Ministries of Health should work out clear strategies that seek to make health services inclusively available and accessible, of good quality, affordable and culturally acceptable. It is particularly important to adopt evidence-based planning which should ensure equitable distribution of health resources throughout all sections of communities.

Governments in Africa urgently need to recognise the importance of health in the overall national development, and support it by making appropriate budgetary allocation to the health sector along other critical economic investments. In addition, the international community also needs to examine their funding policies over the last decade or so, which have resulted in stagnation of financing of reproductive health especially family planning programmes.

[ii] Equinet (2007). Reclaiming the Resources for Health: A regional analysis of equity in health in East and Southern Africa. Fountain Publishers Kampala, Uganda.

[iii] Figures based on gross approved expenditure (2007/8 – 2010/11) and gross estimates (2011/12). Figures indexed to inflation at 2007 CPI.

[v] Kenya National Bureau of Statistics (KIHBS) BASIC REPORT – www.knbs.or.ke/pdf/Basic%20Report%20(Revised%20Edition).pdf

[vii] Davidson R. Gwatkin (2003) Free Government Health Services: Are They the Best Way to Reach the Poor?

Cash for contraception? Photo: Edgar Mwakaba/IRIN

Cash for contraception? Photo: Edgar Mwakaba/IRIN